Why the BSP Cut the Philippine Banking System's Reserve Requirement Mandate

The BSP cut the Reserve Requirements mandate for banks to its lowest level. Why? Because of the escalating strains in bank liquidity conditions from the transformation of their assets.

The whole profit of the issuance of money has provided the capital of the great banking business as it exists today. Starting with nothing whatever of their own, they have got the whole world into their debt irredeemably, by a trick. This money comes into existence every time the banks 'lend' and disappears every time the debt is repaid to them. So that if industry tries to repay, the money of the nation disappears. This is what makes prosperity so 'dangerous' as it destroys money just when it is most needed and precipitates a slump. There is nothing left now for us but to get ever deeper and deeper into debt to the banking system in order to provide the increasing amounts of money the nation requires for its expansion and growth. An honest money system is the only alternative—Frederick Soddy, Nobel Prize in Chemistry

In this issue

Why the BSP Cut the Philippine Banking System's Reserve Requirement Mandate

I. Why the BSP’s RRR Cut?

II. The Inflation Cycle and Non-Performing Loans (NPLs)

III. Philippine Banking System’s Asset Transformation

IV. Paying the Price of Rescues, Banks Morph into Speculators

V. Liquidity Drain from Record Held-To-Maturity (HTM) Assets

VI. How Effective have the Previous RRR Cuts been?

Why the BSP Cut the Philippine Banking System's Reserve Requirement Mandate

I. Why the BSP’s RRR Cut?

BSP, June 8, 2023: The Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) will implement a reduction in the reserve requirement ratios (RRRs) by 250 basis points (bps) for universal and commercial banks (U/KBs) and non-bank financial institutions with quasi-banking functions (NBQBs), 200 bps for digital banks, and by 100 bps for thrift banks, rural banks, and cooperative banks. This measure shall bring the RRRs of U/KBs and NBQBs to 9.5 percent, digital banks to 6.0 percent, thrift banks to 2.0 percent, and rural and cooperative banks to 1.0 percent. The new ratios shall take effect on the reserve week beginning 30 June 2023 and shall apply to the local currency deposits and deposit substitute liabilities of banks and NBQBs. The reduction in reserve ratios is intended to coincide with the expiration of alternative modes of compliance with reserve requirements by end-June 2023 and thereby ensure stable domestic liquidity and credit conditions. This operational adjustment is in line with the BSP’s ongoing efforts towards a more active and flexible approach to liquidity management through market-based monetary operations. This includes the inaugural offering on 30 June 2023 of the 56-day BSP Bill, which serves as an additional instrument for absorbing system liquidity. The BSP emphasizes that the lower reserve requirements do not constitute any shift in the BSP’s monetary policy settings.

In the week of May 12-18, the available reserves of commercial banks amounted to Php 1,695,242 million, while required reserves totaled Php 1,656,007 million. The sizeable cut may represent an estimated Php 410 billion of funds made available to the banking industry (the media estimated a ballpark figure at Php 325 billion).

The June 2023 cut pushed RRR levels to the lowest ever. As a side note, the rules of the RRR policy have evolved over time.

Two other crucial factors from the announcement. One, the policy represents the expiration of some relief measures associated with reserve requirements, and second, it "do not constitute any shift in the BSP’s monetary policy settings".

As the Philstar described, "Banks are required to hold a certain amount of cash as standby funds, which do not generate returns. By cutting the RRR, banks are now allowed to deploy more funds for lending and investments."

Indeed. Because the cuts signified a move from one relief policy to another, it did not factor in monetary injections directly from the BSP and the banks, so technically, there was no change related to the interest rate stance.

But as the media described, the banks may use the released money for lending or credit expansion.

The thing is, because banks could use the released reserves to lend and indirectly influence interest rates, the RRR cut, thus, represented a tacit credit easing measure.

Besides, under this premise, why would banks require RRR cuts if they had sufficient funds to support their current operations?

A better question would be, why did the BSP cut RRR?

The simple answer is that liquidity strains continue to hound the banking system.

Bluntly, banks have insufficient enough funds.

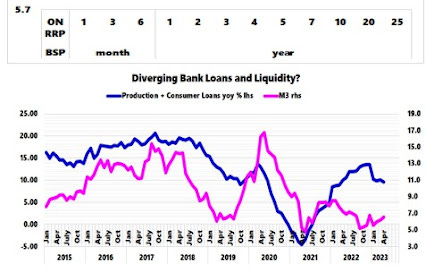

Figure 1

That’s right.

Mounting liquidity pressures have been evident in the BSP's metrics, such as cash-to-deposits and loans-to-deposits ratios. And it is not an anomaly; the downshift has signified a long-term trend. But it has accelerated this year. (Figure 1, topmost chart)

Further, treasury traders have priced in a significant tightening, as exhibited by a negative yield curve. (Figure 1, middle window)

Aside from the entire spectrum, which has been below the BSP ON RRP, short-term yields have been higher relative to the belly and flat against the longer end. Of late, the domestic curve has been steepening, but still negative.

Why this?

Although banks have been lending, the slow recovery of M3 money supply growth indicates possible increasing strains in bank liquidity. (Figure 1, lowest pane)

Further, the aggregate Universal Bank lending growth has been moderating. It was up by 9.6% in April but has slowed significantly since the November 2022 peak of 13.6%. But thanks to the vigorous growth of consumer loans—which has partly offset the decline in production loans—total bank lending growth remains upbeat.

In the meantime, the recent surge in time-deposit growth (48.6% in April) reflects people with excess savings locking into higher yields. Time deposits accounted for 19.7% of M3 in April. M3 has barely risen with the recent recovery of bank lending.

The slowing lending growth contributes to the escalating slack in liquidity growth.

II. The Inflation Cycle and Non-Performing Loans (NPLs)

But there are some developing twists.

Non-performing loans (NPL) appear to have bottomed and exhibit signs of a re-emergence. Consumer loans represent part of this.

As previously pointed out, the weakest link in consumer loans has been salary loans, which NPLs have recently surged.

And this could spread to cover a broader array of the banking system's portfolio.

Again, for an economy heavily dependent on leverage, abating loan growth translates into a slowing economy, which siphons financial liquidity that magnifies credit risk. Mounting cases of NPLs are consequences of this process.

The public has barely figured out that the latest resumption of bank lending hasn't been because of the industry's health but from political intervention.

In particular, the BSP imposed unprecedented relief measures on banks, purportedly to shield the economy from the pandemic recession. While this rescue package effectively disguised embedded risks, it gave leeway to the banks to restart their lending operations.

But inflation affects bank operations.

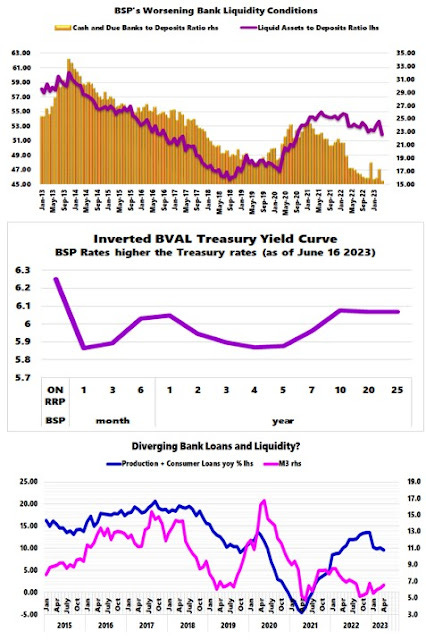

Figure 2

The first wave of the present inflation cycle sparked the uptrend in bank NPLs. (Figure 2, upper graph)

The second and current wave found latitude in these relief measures, which held back the industry's predicament.

But with the CPI currently rolling over, signaling decreasing liquidity, NPLs appear to have bottomed.

Therefore, the next wave of rising NPLs could be due soon if history should rhyme.

Interestingly, loan loss reserves, which ironically developed a wide gap with NPLs, only since 2020, have started to rise too. (Figure 2, lowest window)

The gap or divergence between them showcases the impact of relief programs on depressing published NPLs and loan loss provisions.

III. Philippine Banking System’s Asset Transformation

Bank investments should also be a cause for concern.

Again, the public barely understands the critical transformation in the bank's balance sheets.

Banks, which used to depend on lending, recently relied on investments for their income. But when the inflation crisis emerged, this approach backfired.

The distribution of the banking system's total assets features this crucial transition.

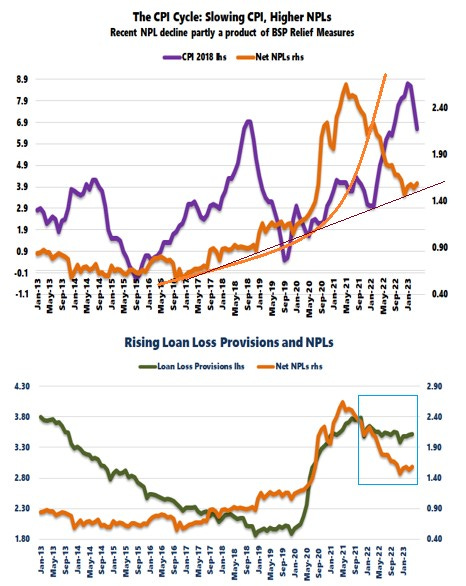

Figure 3

The loan portfolio share peaked in October 2018, then plunged in March 2020 in response to the despotic policies embraced by authorities during the pandemic, which resulted in a deep recession. (Figure 3, topmost chart)

Cash reserves, meanwhile, have been on a cascade since 2013. It spiked in response to the BSP's unparalleled liquidity injections in 2020, but this has faded.

On the other hand, banks used these injections to pile up on financial assets in 3Q 2020. From that moment, financial assets, which accounted for 95.6% of investments last April, not just mounted a tremendous comeback, it became the fountainhead of the industry's earnings during the recession.

IV. Paying the Price of Rescues, Banks Morph into Speculators

The rescue policies also reshaped the industry's incentives. Banks became dependent on such political measures.

So aside from liquidity injections, the BSP's record low-rate regime likewise allowed banks to amass financial assets, which buoyed bank’s total assets.

It is not just banks, even Other Financial Institutions (OFC) became the principal buyers of bank stocks as announced by the BSP (April 28): "In particular, the OFCs’ claims on DCs expanded owing mainly to the growth in the sector’s deposits in banks and holdings of bank-issued equity securities."

Low rates allowed banks to pay lower rates to depositors. It also cushioned or supported collateral prices, which permitted borrowers to refinance at ridiculously cheap rates.

Simultaneously, relief measures provided a backstop to the industry through reduced regulatory, operational, and capital requirements, which also diminished the industry's transparency.

Because of all these political actions, banks morphed into speculators.

And speculation has led to published losses and decreasing investments. In April, accumulated market losses amounted to Php 83.754 billion lower than the record Php 146.06 billion in October 2022. In the meantime, total investment growth slowed to 10.61% about a third from the 30.35% pinnacle in July 2021. (Figure 3, middle and lowest charts)

In turn, these losses and investment pullback compounds the liquidity strains in the financial system.

V. Liquidity Drain from Record Held-To-Maturity (HTM) Assets

And because politics are subject to diminishing returns, rising inflation, which brought upon higher rates, prompted banks to hide their losses through accounting hocus pocus. While banks declared part of their speculative market losses, their "Held to Maturity" (HTM) assets, which are not mark-to-market, constituted the biggest share.

The BSP admitted that HTMs vacuum liquidity in their 2017 Financial Stability Report (p.24). [bold original]

Banks face marked-to-market (MtM) losses from rising interest rates. Higher market rates affect trading since existing holders of tradable securities are taking MtM losses as a result. While some banks have resorted to reclassifying their available-for-sale (AFS) securities into held-to-maturity (HTM), some PHP845.8 billion in AFS (as of end-March 2018) are still subject to MtM losses (Figure 3.8). Furthermore, the shift to HTM would take away market liquidity since these securities could no longer be traded prior to their maturity.

HTMs began their upside even before the first wave of this inflation cycle in 2013. Remember when money supply growth went on a tear, surging by 30% for ten consecutive months, which caused an upside bout of inflation in 2014? Then, according to the politicians, the garlic crisis was the culprit.

Because of the deflation (negative CPI in September & October 2015), which later became evident through the sprouting vacancies in shopping malls (2017), banks embarked on an indirect Quantitative Easing (QE) by stockpiling domestic Treasury securities (Net claims on Central Government--NCoG).

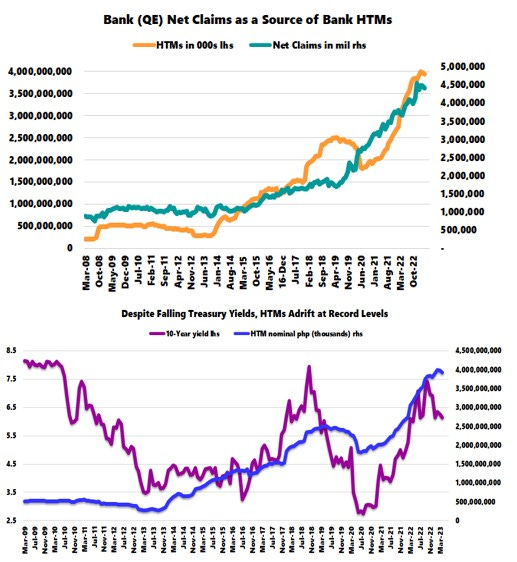

Figure 4

As a result, today's record HTMs represent a mirror of the historic bank NCoG. (Figure 4, upper graph)

Yet, today, HTMs have failed to match the declining 10-year Treasury yields. (Figure 4, lower chart)

And as the BSP noted, since HTMs siphon liquidity, record HTMs extrapolate to a substantial liquidity drain in the system.

Also, if there are any lessons from the 2023 US banking crisis, HTMs played a substantial role.

Add to the record HTMs, the BSP's liquidity dilemma has further been reinforced by the declared mark-to-market losses, rising NPLs, slowing credit expansion, and "higher for longer" rates.

VI. How Effective have the Previous RRR Cuts been?

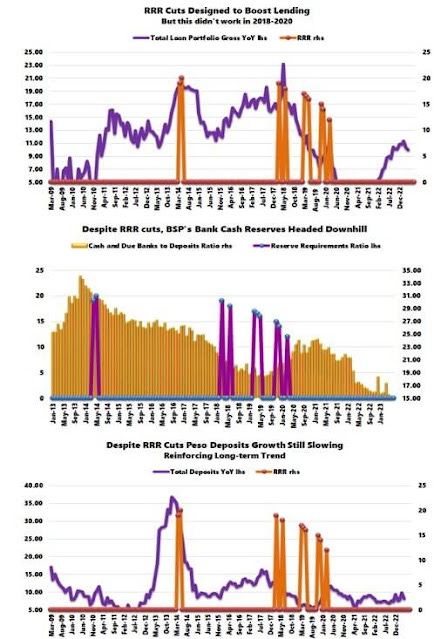

The BSP went into a Reserve Requirement Ratio (RRR) chopping spree from March 2018 to March 2020, lopping off 800 bps or 8% from 20% to 12%.

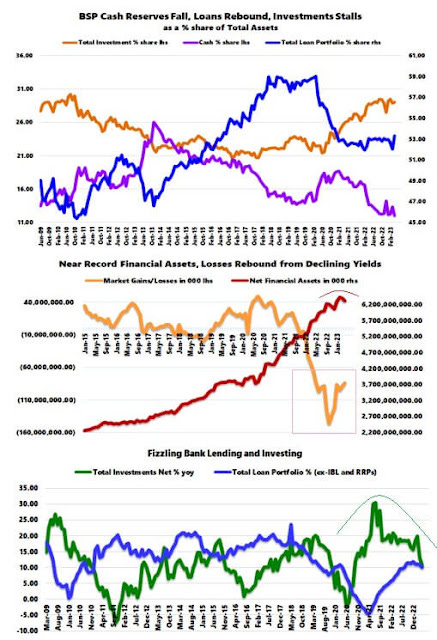

Figure 5

Yet, has this supported the BSP's objectives?

The loan, liquidity, and deposit metrics tell us a different outcome. (Figure 5)

As it is, a chunk of the recent bank lending recovery was due to pandemic relief measures.

Meanwhile, liquidity injections temporarily boosted cash and deposits in 2020—these have faded.

For the same reason, the BSP implements RRR cuts anew—which should be a splendid example of "doing the same thing and expecting different results."

So if history repeats, June RRR cuts will unlikely deliver the desired goodies because the BSP barely deals with its cause. They only see the symptoms, which they call liquidity "mismatches."

In this way, having adequate liquidity will remain a formidable challenge to the banks and the BSP.

Worst, with 9.5% left for bank reserve requirement, the BSP has been draining its toolkit.

But will this time be different? Will 9.5% be the magic number that eradicates these "mismatches?"