Philippine Economy: Bullish Forecasts, Bearish Markets; Volume Precedes Price: The PSE’s Sectoral Performance as Exhibit

The Philippine financial markets seem to contradict the avalanche of optimistic economic forecasts. From the PSE's perspective, falling volume from corroding savings has weighed on price levels.

The problem is those clinging to a world of artifice lose the ability to deal with the real world. They believe that maintaining their fake facade is a substitute for dealing with reality, and so they lose the practice of dealing with the real world via difficult solutions that demand sacrifices and trade-offs—Charles Hugh Smith

In this issue

Philippine Economy: Bullish Forecasts, Bearish Markets; Volume Precedes Price: The PSE’s Sectoral Performance as Exhibit

I. Cognitive Dissonance from Bullish Forecasts, Bearish Markets

II. PSE: The Significance of Volume Driven Price Levels: Jan-May Data

III. Volume Precedes Price: The PSE’s Holding, Property, and Financial Indices

IV. Price-Volume Index Distortions: Industrials, Services, and Mining

V. The Other Side of Volume is Savings

VI. The Fading EPS Boom

Philippine Economy: Bullish Forecasts, Bearish Markets; Volume Precedes Price: The PSE’s Sectoral Performance as Exhibit

I. Cognitive Dissonance from Bullish Forecasts, Bearish Markets

Despite the constant barrage of rosy forecasts on the Philippine economy, has anyone ever considered why the domestic financial markets have deviated from these? Or, the falling peso, rising rates affecting fixed-income securities, and even the bear market in stocks have defied them.

We get it when people become frustrated with their financial investments.

But the conflicting beliefs and the cognitive dissonance that prevails in the public's mindset spurs confusion and emotional disorders.

Let us spell out some of the perplexities.

The prominent description of the domestic economy is that it is consumer-driven.

But spending means exchange. It isn't possible to conduct trade ex-nihilo (out of nothing). The consummation of a trade translates to the interaction of demand (buyer) and supply (seller). Someone buys or pays for a service or good at an agreed price. As a medium, money funds such transactions.

Say’s Law (or the Law of Markets) as explained by the great Ludwig von Mises,

Commodities, says Say, are ultimately paid for not by money, but by other commodities. Money is merely the commonly used medium of exchange; it plays only an intermediary role. What the seller wants ultimately to receive in exchange for the commodities sold is other commodities. (Mises, 1950)

There can be no consumption without goods and services. We, therefore, produce to consume.

Instead, the massive twin (fiscal and trade) deficits tell us the Philippines indulges in profligacy: it spends more than it produces. And those deficits are funded by taxes, inflation, and credit (domestic, foreign savers, and or fiduciary media).

It is the same with the stock market. Each transaction requires funding. How? Well, it comes from people's—individuals or commercial entities—disposable income or savings and or borrowings.

When income grows more than expenses, an individual may allot such surpluses for savings or investments, such as acquiring stocks or (corporate/government) bonds or putting up or expanding a business.

After all, since investing in stocks requires savings (and/or access to credit), evaluating whether economic conditions would lead to an increase or decrease in savings should be a prerequisite.

As a side note, local financial markets are anachronistic compared to their sophisticated counterparts in advanced economies. In this regard, domestic stocks are principally funded by savings.

Some relevant questions:

Is an inflationary environment conducive to savings?

Will sustained increases in government spending lead to increases in income and savings or will it only transfer resources from the private sector to the government?

Will credit-financed asset bubbles lead to the enhancement of the people's standard of living?

II. PSE: The Significance of Volume Driven Price Levels: Jan-May Data

With this in mind, let us review how the May performance of the PSE reflects on such dynamics.

The primary bellwether, the PSEi 30, ended May down 2.23% (MoM), 4.4% (YoY), and 1.36% (YTD).

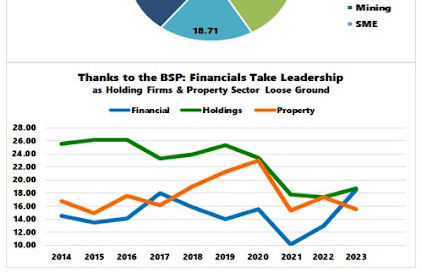

Figure 1

The aggregate 5-month (YTD) peso turnover plunged by 12.03% to Php 694 billion, a low last reached in the 2020 pandemic crash. (Figure 1, topmost graph)

But the YTD 2023 volume was 11.62% higher than 2020's Php 622 billion.

The volume indicated includes special block sales.

Importantly, the PSEi 30 closed at 6,477.4 last May 2023 compared with 5,838.8 in May 2020, or higher by 10.94%.

So, volume and index in 2023 were still up relative to the lows of 2020.

If anything, despite the relentless orchestrated push to get the PSEi above 6,500, it closed lower in May primarily due to the scanty buying power.

As such, should volume continue to slow, it shouldn't be a surprise that the PSEi 30 would most likely mirror its decline.

III. Volume Precedes Price: The PSE’s Holding, Property, and Financial Indices

As chart technicians would say, volume precedes price.

So how did volume influence prices?

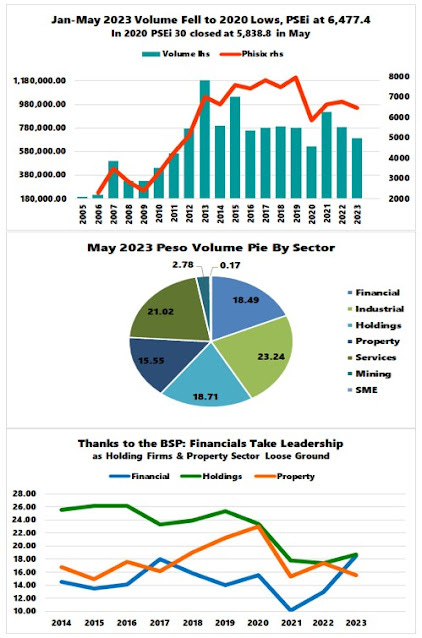

Partitioning May's volume by sector, the holding firm's sector (18.71%) edged out financials (18.5%) for the largest share. This chart represents May data only. (Figure 1, middle window)

The leading role of the holding firm represented a trend.

But the downtrend in the YTD holding firm's volume share since 2014 translates to loosening its grip over the leadership. (Figure 1, lowest chart)

Figure 2

The property sector almost took the lead, but the pandemic abruptly abridged the public's interest in 2020. And so, its share of YTD volume plunged along with its index. (Figure 2, upper window)

In the meantime, the YTD volume share of financials rallied to the second spot—thanks to the BSP's various bailout measures. (Figure 2, lower chart)

Considering that both were beneficiaries of the BSP bailout, the paradox was the divergence of market allocation to these interrelated sectors.

The market pushed financials higher while it sold down the property sector.

Perhaps, some of this may have involved rotational dynamics—or rebalancing or shifting of equity exposure from the latter in favor of the former.

The opposing directions of their respective volume, which directed the price level of the indices, exhibited the market's discordant perception.

Of course, banks were direct recipients of the BSP largesse, while the property sector signified the second-order indirect beneficiaries.

Figure 3

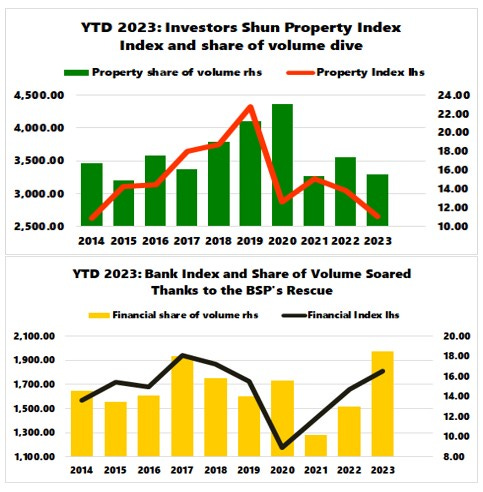

From another angle, the sectoral performance relative to the PSEi 30—represented by its ratio—exhibits such contrasting actions.

While the property sector to the PSEi 30 ratio continued to plumb down to 2016 levels in May, the bank index was a notch below its all-time highs. (Figure 3, topmost graph)

Ironically, this market may have forgotten that the property sector is the largest borrower of the banks!

Despite the recent decline, the property sector has the largest share (19.9%) in total bank loans (UC, Rural, and Thrift banks). In pesos, it was at an All-Time High (ATH) in April! (Figure 3, middle pane)

Or perhaps, such deviation in the market could have signified the BSP's implicit edict or a collaborative effort of the industry.

After all, the BSP recently disclosed that Other Financial Corporations (OFCs) were buyers of bank shares in Q4 2022. Why would OFCs jointly buy bank shares? Coincidence? Or has this signified directed action?

IV. Price-Volume Index Distortions: Industrials, Services, and Mining

There is an array of price distortions in other sectors.

The share of the service sector spiked in 2021, while industrials in 2022. Unlike the financials, unfortunately, the spikes were ephemeral. (Figure 3, lowest pane)

Figure 4

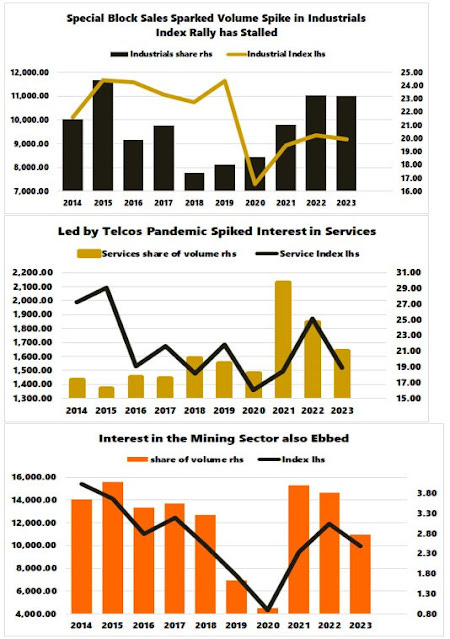

Huge special block sales of AP, FGEN, and MONDE propped up the sector's volume in 2021. EAGLE's tender offer for its delisting also boosted its volume in 2022. (Figure 4, topmost chart)

In this respect, because special block sales accounted for off-mainboard trades, the sector's price levels were hardly affected.

Or, this explains why prices were influenced least by the volume spike.

The earlier gains signified a spillover from the BSP's injections that percolated into the PSE's broader universe.

On the other hand, pandemic remote work policies influenced interests in the telcos, which bolstered volume and the services index. (Figure 4, middle window)

But as the economy reopened, interest in the sector waned upon the recalibration of work conditions into "hybrid" and "return to the office."

As it happened, radical changes in the political environment materially influenced both volume and price activities.

Likewise, interest in the mining sector also resonated with the general sentiment.

But since the sector has been considered highly speculative, magnified volatility, as reflected in price and volume, exhibits this sentiment. (Figure 4, lowest diagram)

Mining, of course, has the lowest share of volume. This discussion excludes the SME sector.

V. The Other Side of Volume is Savings

Figure 5

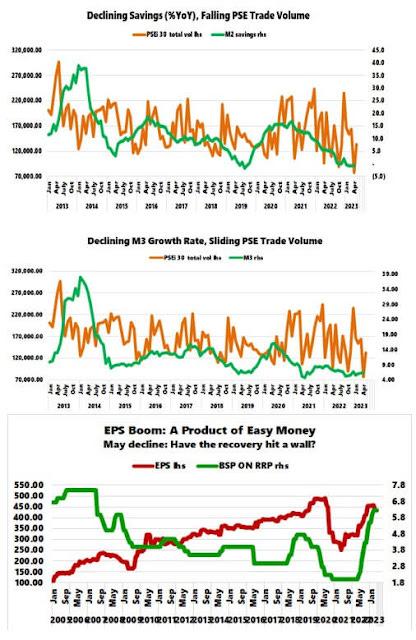

In all this, the evidence of the importance of savings exhibited by the corrosion M2 savings, which in turn led to the PSE's deteriorating volume/turnover. The popular money supply benchmark, M3, illustrates a similar relationship. (Figure 5, top and middle charts)

Again, unless conditions warrant improvement in disposable income and savings, the PSE will remain under pressure, regardless of how a few entities attempt to manage the PSEi 30's price level—mainly via pre-closing pumps—which, unfortunately, undermines the market's price discovery function.

VI. The Fading EPS Boom

In closing, the BSP & PSE published the May price-earnings ratio (PER), which on the surface, looked "cheap."

But the earnings per share (eps) exhibited a second straight month of decline. (Figure 5, lowest graph)

Since misstatements of balance sheets seem to have been given a free pass by authorities and the private regulator, this urges us to question the credibility of the published financial performance of listed firms.

Even if these are accurate, it provides an insufficient perspective of the actual conditions of the corporate bottom line.

The thing is, debt has driven the PSEi 30’s top and bottom-line growth. But debt has outgrown income consistently for several years now.

Even the BSP is aware of this risk. (bold mine, cited chart figures edited)

Based on the audited financial statements of the 148 Philippine Stock Exchange (PSE)-listed non-financial corporations (NFCs), the growth of interest expense (IE) has outpaced the rise of earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT). In addition to the rate of growth, the ratio of IE to EBIT shows a rise from 14.5 percent at the start of the first quarter of 2016 to 22.6 percent as of March 2019, with a high of 27.8 percent in December 2017. The same companies have also reported lower profitability with respect to return on assets (FSCC-BSP, 2019)

And that was for the year 2018. Growth of debt since then has been turbocharged.

Further, the eps boom depended on a regime of perpetual easy money from the BSP.

If the age of inflation 2.0 has indeed mounted a comeback, then the free lunch that has backed this artificial boom has culminated.

___

references

von Mises, Ludwig, Lord Keynes and Say's Law, The Freeman, October 30, 1950, Mises.org

FINANCIAL STABILITY COORDINATION COUNCIL, 2018 H1–2019 H1 FINANCIAL STABILITY REPORT, September 2019 p 13, bsp.gov.ph